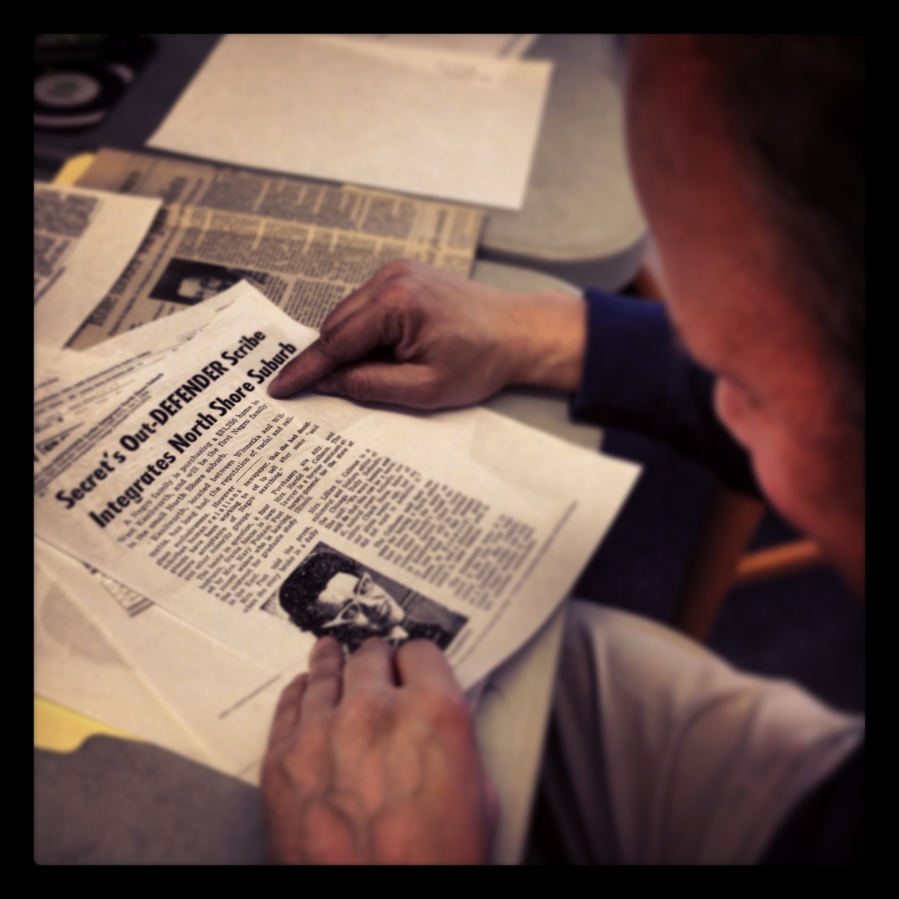

—By Dino Robinson

While William Twiggs was a locally, and historically well documented businessman and an active member of several organizations, little has been mentioned about his wife, Martha Twiggs. Family decedents mention that she had a home-based business, selling wigs for women made from natural hair first at Oak Avenue near Church Street in Evanston then later in a storefront next to her husbands print shop on Emerson Street. There, she marketed her own product, “Twiggaline”, a hair growth product.

In 1916, Madam C. J. Walker’s came to Evanston to deliver her Lecture on “The Negro Woman in Business” at both Second Baptist and Ebenezer A.M.E. Church.1 In her lecture, Madam Walker “Urges her Sisters to Rise above the Wash Tub and Cook Kitchen and Make a Place in the Commercial World.”2 One wonders if Martha Twiggs may have been inspired by the lecture and ventured off to follow the shared tenants from Madam C. J. Walker lecture. Shorefronts only wish is that someone may have a sample of the Twiggaline package or product today.

Several years ago, Shorefront began acquiring samples of contemporary “products” for Shorefronts archive that illustrate the entrepreneurial ethics of these North Shore communities. Which leads us to wonder . . . who we have not come across at this time that have produced their own product for distribution . . .

Carrying the tradition of Martha Twiggs today includes, Georgia Parker, Larry Alexander, Ashley Askew-Bell and former Evanston resident Lauryn N. Nwankpa, all have products geared to hair and skin care.

Lauryn, through her business Hair To There LLC, produces a product for natural hair care. She markets her product on line, at related conventions and other showcase venues. Recently, she redesigned her packaging and website and included an infomercial focused on natural hair care.

A degreed chemist, Georgia Parker has over 20 hair and skin care products under the name Ashley Lauren Products. Ashley Lauren at one time had a storefront on Davis Street in Evanston across from the post office. Now, focused on distribution, her products can be purchased on line and at a few retail outlets in the Chicago area.

Scrubfusion owner Ashley Askew-Bell, offers several body scrub products, beard oils and candles on her site for both men and women. Customers can also request custom orders for special events.

Patent holder, and former Salon owner, Larry Alexander, also known as Mickey III, developed an applicator instrument for laying relaxer in a clean and consistent manner under the name AppliTech. Video demonstrations showcase the proper use of his patent protected tool.

A couple of Food and edible products are offered by barbeque owner Hecky Powell and Chef Journey Shannon.

A chocolatier, Journey Shannon has a line of chocolates and other crafted editable foods under the name Noir d’Ebene, and can be ordered online, at select events, fairs and industry shows.

And of course, Heck’s Barbeque line of sauces, spices/rubs and most recently added, soda. The product can be found in retail, online and at his place of business. Proceeds from his “Juneteenth” soda sales, helps to fund projects through the family’s Forrest Powell Foundation.

Shorefront is sure that it is missing so many more entrepreneurs who have packaged products. Though this article focuses on products, we know there are some interesting inventors who lived in the North Shore area. Industrial Designer Charles Harrison who’s work with Sears has designed many iconic items. Evanston residents Delbert Alexander Sr. and Jr. both have created workable prototype machines (baseball and tabletop bowling). In the 1950s, Glencoe resident Asa Taylor prototyped what would lay the foundation of the modern hydraulic hospital beds used today . . . But that is another article and initiative in hopes to acquire prototypes if they still exist.

Sources:

- Chicago Defender: “Will Lecture in Chicago”, January 29, 1916, p. 8; “Prairie State Events. . . ,” By J.R. Moore, Feb. 12, 1916, p. 5; “MME. C. J. Walker Royally Received Here”, Feb. 19, 1916, p. 2.

- Indianapolis Freeman, “The Negro Woman in Business”, September 20, 1913, p. 1.