—by Dino Robinson

There are moments in this country’s history when movements emerge in response to social conditions surrounding us. Our current generations “Black Lives Matter” came to life defined by the inequity of law enforcements treatment of people of color. The Civil Rights movement was defined by the activities of the 1950s and 60s. Fighting the establishment of Jim Crow during the Reconstruction era, led to the formation of the Niagara Movement in 1905.

Established on February 12, 1909, The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People was birthed out of the 1905 Niagara Movement. In Evanston, with a population of a little under 1,200 Black residents, had just begun to take action against the growing local Jim Crow establishment. Local and national newspapers took note while Evanston was compelled to maintain the image of a “sanctified” town, all while Jim Crow was becoming the norm. Evanston’s Black residents took action, challenged society, questioned government — and made headlines.

May 6, 1903 (Chicago Tribune)

“Evanston Blacks Fear Wave of Race Prejudice”:The article tells of a certain colored man frightening women and calls upon the colored people to keep their brother at home. The article is headed, “A Rope Might Do,” and the colored people in Evanston take it seriously. . .

January 22, 1904 (Chicago Tribune)

“North Shore Towns Aroused: Influx of Negroes Alarms the Residents of Evanston, Wilmette, Winnetka and Glencoe”: .. . As a solution of the problem suddenly presented, Evanston citizens are reviving the old scheme of a town for negroes, to be located near Niles Center. To this it is proposed to deport objectionable characters.

February 7, 1906 (Chicago Tribune)

Charges Stir a Post office: Race Discrimination on of accusations at Evanston – Trouble is said to arise out of Employment of Negro Carriers”:

. . .DePugh accused Peterson frequently of discrimination against the colored carriers and is said to have made frequent threats that he would “tell what he knew.” Several times he was threatened with dismissal.

August 26, 1911 (Chicago Defender)

“Jim Crow Cars for Cultured Evanston”:Evanston Southern (White) Society Successful in Jim Crow Theater, will now resort to Jim Crow street cars — The Unwarranted segregation a blight in cultured Evanston; Where there are as many churches as schools. The Rights of the negro citizen should be demanded and respected; the matter peaceably adjusted, once and always— The constitution of the United States must be respected and guarded as strictly as the “Monroe Doctrine” was in the case of Cuba and the Mother Country.

In the same issue:

“The Segregation Equivalent at Evanston”:. . .Whether Evanston is to continue to maintain a clean, respectable, unbiased community such as she bears by reputation will be watched editorially by the Defender with great interest.

September 2, 1911 (Chicago Defender)

“Forces are Fighting Jim Crowism”:Rev. H. S. Graves of Ebenezer AME and Rev. E.H. Fletcher of Mt. Zion Baptist church charged against Jim Crowism from their pulpits on last Sunday evening. . .

September 9, 1911 (Chicago Defender)

“Colored People Admitted in All Parts of Evanston Theater”:The management of the Evanston theater came into camp with a flag of truce begging mercy of the butler of the Northwestern railroad president, Dr. and Mrs. Garnett, and Attorney Auter for trying to keep them out of a decent place to sit in their playhouse…

November 4, 1911 (Chicago Defender)

“Wealthy Evanstonians Speak in Defense of their Lethargy. . . Dr. W.F. Garnett cool but determined for Justice”: . . . [Long op-ed. ending with a listing of local leaders] – Respectfully submitted – Dr. W.F. Garnett, Samuel J. Cannon, William H. Twiggs, Richard C. Williams, James P. Hill, Thomas F. Richardson, Frank Davenport, Charles C. Breckenridge, Dr. Arthur D. Butler, Adam P. Perry, William F. Cromer, Thomas H. Cotton, Charles Morris, Joseph Prather, Robert T. Milner, Henry Butler, Sandy Trent, D.W. Richardson, John R. Auter, Charles B. Scruggs, J. H. Blackwell, Ernest Burns.

February 10, 1912 (Chicago Defender)

“Evanston Theater Sued by Mrs. Garnett”: Mrs. Helen W. Garnett, wife of Dr. Garnett, who lives in Evanston. The suit was brought for $500 in the circuit court. Hon. E.H. Morris is the man behind the law

June 22, 1912 (Chicago Defender)

“Evanston Theater Still Bars Negroes”:On last Saturday evening the Evanston Theater company again showed that it did not want and would not have Negroes sitting on the ground floor. . . Mr. Vance informed her that they would not tolerate Negroes on the first floor.

August 7, 1913 (Chicago Tribune)

“Wilmette Takes Trail of Negroes”:Village residents call meeting for Saturday Night to discuss “Invasion”. . . Demanded property list. . . If Black men are revealed as purchasers means of ousting will be considered. “It is expected Mr. Barker will be invited to the meeting Saturday night and asked to explain what guarantee he has that the village will remain white.

May 6, 1916 (Chicago Defender)

“Demands Right to Choose Seat”:Evanston, IL, May 5—John Smith, who was arrested after he had refused to take a seat to which he was directed in an Evanston movie show, today prepared to make a fight against the “Jim Crow” rules which are enforced in a number of similar places. . .

The Crisis Magazine, established in 1910 as the official organ of the NAACP, reported some activities in Evanston. Of note, the August, 1918 issue (Vol 16, No 4), published a roll of 26 members in Evanston. The April 1919 issue (Vol 17, No 6) published a roll of 59 members in Evanston. By the end of 1919, the Crisislisted a total of 11 active chapters of the NAACP in the State of Illinois and included Evanston, Illinois.

June 28, 1919(Chicago Defender)

Professor A.C. McNeal was the principal speaker at the NAACP meeting, held at the Emerson Street Y . . .. Dr. W. F. Garnett was master of ceremonies. Prof. W.W. Fisher was elected president of the NAACP and Mrs. Elizabeth Croford [sp] Williams secretary.

The Evanston chapter worked toward making an organized impact within Evanston with efforts to show formal structure:

April 30, 1921 (Chicago Defender)

“Mrs. G. DeBaptist Ashburn spoke at the “Y” Thursday evening in the interest of the NAACP and reorganized the branch in this city.

Though the early charter members of the Evanston NAACP are not clear, it is noted that within the combined early newspapers and publications, several names had appeared. Among them were the following:

Dr. William F. Garnett

Hellen W. Garnett

Rev. Horace Graves (Ebenezer)

Rev. E.H. Fletcher (Mt. Zion)

Dr. Isabella Garnett

Dr. Arthur D. Butler

William H. Twiggs

Prof. W.W. Fisher (served president, 1919)

Elizabeth Croford [sp] Williams (secretary, 1919)

Dr. R. M. Young (served as president, 1921)

W.M. Tate (V.P. 1921)

S.C. Nichols (secretary, 1921)

J.E. Moor (asst. sec., 1921)

J. Malone (treasurer, 1921)

By 1924, This Evanston chapter dissolved. However, a renewed interest in chartering a new Evanston branch NAACP was reported in the November 10, 1927 issue of the Evening News Index.

“Colored people of Evanston May Join Association: Plan to Organize Unit at Sunday Meeting”. . . Evanston colored citizens let by I.G. Roberts and Albert C. Ivole [sp], will meet at the Emerson Street Church to organize themselves into a unit of the NAACP. . . Three years ago, the Evanston unit disbanded, and Monday evening the group will make plans to apply for a new charter.

Then in November, 1928

“Negro Association to Launch Member Drive at Meet Tomorrow”:Tomorrow the Evanston branch of the NAACP, which has recently been organized through the efforts of E.D. Seals, will launch a drive for members. . . The Rev. William J. Weaver, rector of St. Andrew’s Episcopal church of Evanston is president of the Evanston Chapter.

A few of the members mentioned in articles after the new charter include the following:

E.D. Seals

Gertrude O’Neill (program chair)

Rev. William J. Weaver (president, 1928)

Edwin B. Jourdain, Jr (his father was involved with the original Niagara Movement)

Daisy Sandridge (former 5thward alderman)

Robert Pettitt (president, 1935)

LeJune Fisher

Claude Cephas

The work of the Evanston Branch NAACP has since been uninterrupted after its new charter in 1928. The early activism of Evanston’s Black community rose to fight against Jim Crow. Today, the Evanston Branch NAACP continues its advocacy for modern Civil Rights. The Evanston branch has had about 25 presidents, and a legion of executives and board members. The past known presidents are as follows:

Dr. William F. Garnett, 1918?

Prof. W.W. Fisher, 1919

Dr. R. M. Young, 1921

Rev. William J. Weaver, 1928

Robert Petitt, 1935

William Wright (dates uncertain)

Clarence Mason, Sr. (dates uncertain)

Lula Harper-Jackson (dates uncertain)

Rev. J. Rayford Talley (dates uncertain)

Dr. Samuel McDonald (dates uncertain)

Charles Worthington (dates uncertain)

William Pyant (dates uncertain)

Dr. Warren F. Spencer, 1957-63

Andrew L. Cooper, 1964-68

Carl E. Davis, 1969-76

Edna Summers, 1977-78

Coleman Miller, 1979-84

Joseph E. Hill, 1984-89

Bennett J. Johnson, 1990

Rev. John Norwood, 1991-92

Coleman Miller, 1993

Hecky Powell, 1993

Fred Hunter, Jr., 1994

Bennett J. Johnson, 1995-2002

George Mitchell, 2002-16

Rev. Michael Nabors, 2017 –

While this is just a summary of the Evanston Chapters, spanning nearly 100 years, there is still much discovery needed, especially for its early local history. Let’s make this happen.

Notes: Oral presentation first delivered at the Evanston Chapter, NAACP Installation Ceremony held at Unitarian Church of Evanston, Sunday, January 22, 2017 written and researched by Dino Robinson, founder of Shorefront. The article was modified for formatting

So we celebrate Juneteenth, celebrating African American freedom, achievement, self-development and remember that we must show respect for all cultures. As Juneteenth celebrations continue across this nation, the events that have transpired back in 1865 in Texas, will not be forgotten. For all of our roots tie back to this fertile soil from which many were delivered to, worked on, built on, and we all should celebrate, a national day of pride that is embodied as Juneteenth.

So we celebrate Juneteenth, celebrating African American freedom, achievement, self-development and remember that we must show respect for all cultures. As Juneteenth celebrations continue across this nation, the events that have transpired back in 1865 in Texas, will not be forgotten. For all of our roots tie back to this fertile soil from which many were delivered to, worked on, built on, and we all should celebrate, a national day of pride that is embodied as Juneteenth.

The

The  Shorefront also facilitated an intern from Dominican University. Nicole Gibby Munguia fulfilled a 40 hour internship in the last quarter of the year that will result in at least one processed project and one article for publication in

Shorefront also facilitated an intern from Dominican University. Nicole Gibby Munguia fulfilled a 40 hour internship in the last quarter of the year that will result in at least one processed project and one article for publication in

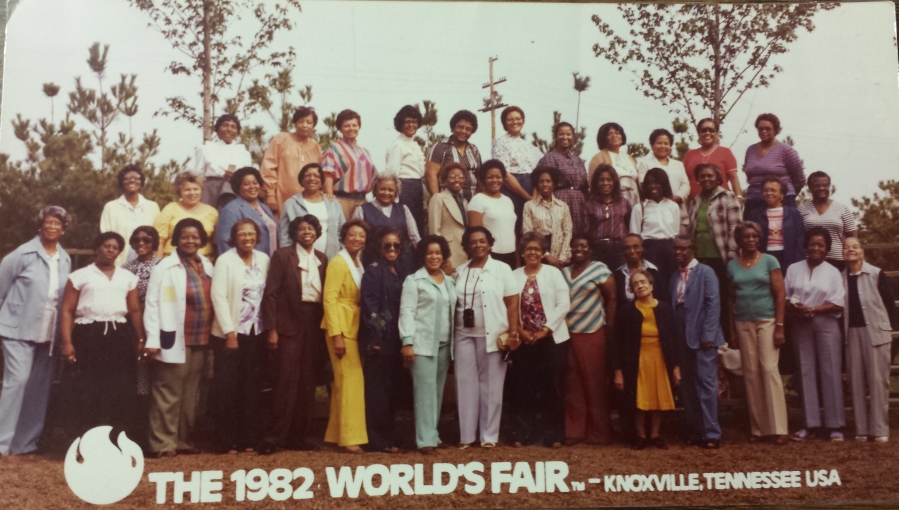

In 2014, we reported a 50% growth of our archives to a little over 100 linear feet. Since then, the holdings have grown to over 175 linear feet— and it is still growing. New collections include the Evanston Neighborhood Conference, North Shore Chapter Jack and Jill, Inc., a significant addition to the Ebenezer A.M.E. Church, Delta Alpha Boulé and North Shore Illinois Chapter of the Links, Inc. archives, and several family archives.

In 2014, we reported a 50% growth of our archives to a little over 100 linear feet. Since then, the holdings have grown to over 175 linear feet— and it is still growing. New collections include the Evanston Neighborhood Conference, North Shore Chapter Jack and Jill, Inc., a significant addition to the Ebenezer A.M.E. Church, Delta Alpha Boulé and North Shore Illinois Chapter of the Links, Inc. archives, and several family archives. Shorefront owes thanks to

Shorefront owes thanks to