—By Celia

I came to work at Shorefront through a circuitous series of realizations and referrals. During the summer of 2017, just before I went to college, I was reading Bryan Stevenson’s Just Mercy on my back porch in Glencoe. I was taken aback by Stevenson’s stories of defending inmates on death row, but equally struck by two of his other ideas: First, that the United States has a long, long way to go in memorializing the horrendous legacy of slavery, and second, that one must be proximate to issues to truly understand them and make a difference.

While reading about the cruelty of systematic incarceration and capital punishment of African-Americans, I couldn’t help but think about to which issues I, a Jewish girl on her back porch in Glencoe, was proximate. Throughout my time in Glencoe’s public schools and New Trier High School, I could count my black classmates on one hand, and had never considered why. Nearly all-white suburbs are not natural; they are the products of deliberate racial discrimination. I had been so close to the issue that I couldn’t see it for what it was. It was time to transform that inability to examine my surroundings to a meaningful proximity, like stepping back from an impressionist painting.

How did my town come to be so white, and what was to be done about it? That was the question I tried to answer with a free summer and the internet at my disposal. I found scans of census records on a genealogy website and hand-counted each black resident from decades of data. Although tedious, I found something important: the black population of Glencoe halved in between 1920 and 1930. What had happened during that time?

I wasn’t sure, and I didn’t know where to go next for my research. I read Robert Sideman’s African-Americans in Glencoe, which illuminated some important sources for me, and interviewed a few residents. I would be starting school soon, and had to table the project to transition to college.

Just a few weeks in, I met Dr. Chatelain, a history professor at my university. She’s regarded as a must-take professor – equally accomplished and devoted to her students. When I told her about my nascent project, she directed me to Shorefront, where she had done research in graduate school. I reached out to Dino, and started to work in the archives when I returned home for the summer.

I really enjoyed organizing sources to be used by future researchers. I categorized letters written by Freedom Summer teachers to their disapproving parents. I sifted through legal notices and memoranda about discrimination by the Noyes Cultural Arts Center. But what interested me the most was a heap of unsorted materials about Glencoe from the 1880s to present day: newspaper clippings, letters, invitations, pamphlets. They proved incredibly helpful in establishing what had happened in my hometown, from its inception to the present. With that arc of history came a set of patterns that made Glencoe the way it is today.

First, Glencoe was always meant to be idyllic. This hasn’t changed much since its founding: Glencoe is situated overlooking a beautiful beach; it’s filled with well-maintained green spaces; the schools are well-regarded and small enough that everyone knows one another; the houses are beautiful and often sell for millions. Such was the vision of its founders, who sought an escape from their busy city lives.

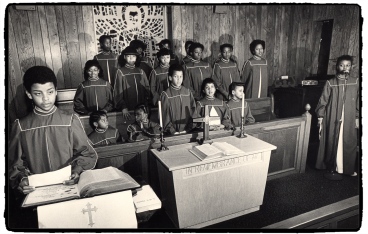

African-Americans bought property in Glencoe from early on in its history. Morton Culver, a local real estate developer, first sold land to blacks from Chicago in the early 1880s. The St Paul AME Church was founded shortly after in 1884. I found a Chicago Tribune article from the same year about a picnic in Glencoe, an event that drew blacks from the city and a number of surrounding suburbs. The picnickers are reported to have sung, “We’ll rest in this beautiful land, / Just along Michigan’s shore / Sing the song of Moses and the Lamb, / And dwell in Glencoe evermore.”

The vision of a blissful suburb seemed, at this moment, accessible to blacks. The air was fresher and the schools, which had always been racially integrated, were better than the cramped ones in the city.

But Chicago’s white elite was also taking notice of this ideal setting. Wealthy white couples started to pine after lakefront mansions for the weekends, and founded country clubs to entertain them during their stays. Eventually, these weekend visitors began to permanently settle in Glencoe.

A critical mass of them took measures to remove black people from Glencoe. In 1919, the Glencoe Homes Association was founded by residents with the intent to “beautify” the town. It bought properties to be resold with what Robert Sideman calls “zoning-like restrictions” to increase the town’s green space and sell selectively to what it deemed “proper” buyers.

In 1927, Glencoe Homes embarked on a project with the town’s government to build a public park. Rather than using the town’s many vacant lots, it would be located in the middle of southwest Glencoe – where the majority of black families lived. After much opposition, the families were forced to settle. The Glencoe Homes Association published an op-ed in the local paper about their disapproval of the “negro colony,” paraded under the headline: “Prevention by ‘Syndicate’ of Blight to Community Saved Realty Values in Millions.”

This is the point at which Glencoe’s black community halved, the enormous dip in the census data. I had sometimes wondered why Watts Park, where I learned to ice skate and had lacrosse practice, was divided by a street in the middle. Wouldn’t it have made more sense for it to be continuous? But nearly all-white suburbs are not natural; they are planned deliberately.

Despite this major fracture in Glencoe’s black population, the suburb continued to be relatively more diverse and progressive when compared to its surrounding suburbs. A.L. Foster, a Glencoe resident and then-Executive Director of the Chicago Urban League, won a case to desegregate Glencoe’s public beach in 1942, while Kenilworth didn’t have a single black resident until 1963.

Glencoe became a small enclave for black residents in an otherwise overwhelmingly white sea of suburbia. Mayor Robert Morris initiated programs to encourage African-Americans to apply for the village’s jobs in the mid-1950s, and the Glencoe Human Relations Committee formed to advocate for open housing and more harmonious race relations. When parents of New Trier students formed Concerned Black Parents in 1977, it met consistently where there was a critical mass of black parents: Glencoe. The group pushed for New Trier’s recognition of Martin Luther King Jr. Day and inclusive teaching at the majority white high school.

Newspaper articles I found from this period struck me as odd. There were multiple articles that profiled Glencoe’s black residents as anomalies in their exposure to such a progressive society. In particular, I found this article bold in its claim to Glencoe as a champion of race relations:

February 9, 1977 (Suburban Trib)

“Assumptions on Race don’t Hold; Glencoe’s 6% Black”: The article rebukes the assumption that Glencoe has no black population, but rather a percentage far below the national average. It also acknowledges that “…a black homeowner will have to sell for a bit less than a white homeowner with a comparable house in Glencoe.” It recognizes that the original sale of property to blacks in Glencoe may have been a scheme to resentfully decrease its property value, but it “backfired and for years Glencoe was a primary source for domestic help on the North Shore.” Such “backfiring” refers only to the quality of life for white residents.

While these articles clung to every testimony and long-time residency of black Glenconians, the population has been declining gradually, but consistently, at about 1% per decade since 1930. One woman whom I interviewed cited the exorbitant housing prices as the main reason that her children didn’t raise their families in their hometown – an obstacle exacerbated by the fact that blacks often sold their homes for lower than they were worth. Another black resident wrote to the Glencoe News in 2004 to lament her inability to return to Glencoe because the homes on her childhood block had been torn down to build houses of twice the value. One might be reminded of the Glencoe Homes Association’s calls to beautify the town, and its consequences.

But economics aside, and with a multitude of studies proving that black families are more likely to live in lower-income areas even if they can afford not to do so, other factors influenced this gradual exodus. In a 2004 Glencoe News article entitled “Black Population Dwindles,” advocates cite widespread “‘steering’ [of] prospective homeowners toward communities that fit their demographic.” Carol Hendrix, a co-founder of Concerned Black Parents, witnessed her community leaving Glencoe over time, saying, “…[T]here was an effort by the builders to engineer the neighborhood.” Angela Hatfield, another resident interviewed in the article, said she was virtually certain that a white family would live in her home after her.

Glencoe is currently 0.7% black. With its green spaces and beautiful beach, its colonial homes and quaint downtown, I can’t help but think of a line from Martin Luther King Junior’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” He writes of the shame and injustice in “when you…see tears welling up in [your six year old daughter’s] eyes when she is told that Funtown is closed to colored children, and see ominous clouds of inferiority beginning to form in her little mental sky, and see her beginning to distort her personality by developing an unconscious bitterness toward white people.” Glencoe is Funtown. While it wasn’t part of the Jim Crow South, it had been closed off to African-Americans in a gradual, de facto manner. Beyond the public policy implications of this injustice, it’s an affront to the dignity of so many.

In closing, I tried to better understand this issue to which I was so proximate. In doing so, I realized just how much history this suburb, of less than ten thousand residents and five square miles, holds. This history was sometimes subject to the reverberations of events far beyond its own scale – the Great Migration, for example – but, on the whole, was largely influenced by everyday people trying to change their hometown. From Morton Culver to A.L. Foster to Carol Hendrix, these individuals transformed the microcosm that is Glencoe, beyond the purview of anything I would learn about in an American History class. I’m grateful for organizations like Shorefront, that safeguard these local histories, and the legacies of those who sacrificed for their vision of a more equitable society.

Sources:

Sideman, Robert A., African Americans in Glencoe: The Little Migration, © 2009, The History Press, Charleston, SC.

Chicago Sun-Times, “Court Opens Glencoe Beach To Negro Family: Injunction Granted Against Official Of Park District”, July 10, 1942.

Suburban Tribune, “Assumptions on Race don’t Hold; Glencoe’s 6% Black”, February 9, 1977.

On Saturday, July 21, 2018, the major event for the Family Rendezvous 2018 introduced the participants to Shorefront Legacy Center, (Shorefront) 2214 Ridge Avenue, Lower Level, Evanston, IL. Morris “Dino” Robinson, Shorefront’s founder, graciously hosted over 50 family members and friends from California, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Missouri, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Texas, and Wisconsin. Evanston residents, Mattie Amaker, Priscilla Giles, and Catherine Johnson, members of the African American History and Genealogy Study Group of Evanston and Afro-American Genealogical & Historical Society of Chicago, attended and offered their expertise.

On Saturday, July 21, 2018, the major event for the Family Rendezvous 2018 introduced the participants to Shorefront Legacy Center, (Shorefront) 2214 Ridge Avenue, Lower Level, Evanston, IL. Morris “Dino” Robinson, Shorefront’s founder, graciously hosted over 50 family members and friends from California, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Missouri, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Texas, and Wisconsin. Evanston residents, Mattie Amaker, Priscilla Giles, and Catherine Johnson, members of the African American History and Genealogy Study Group of Evanston and Afro-American Genealogical & Historical Society of Chicago, attended and offered their expertise. Shorefront’s welcoming spirit encourages investigating, learning, and researching. This repository immediately immersed participants into Evanston’s African American history. The Shorefront Journal covers spread out across a wall displaying faces from the community. Another wall display highlights various photos and artifacts. The meeting room contains artifacts, books, and an ongoing video presentation. In the midst of all of these displays stands the Archives.

Shorefront’s welcoming spirit encourages investigating, learning, and researching. This repository immediately immersed participants into Evanston’s African American history. The Shorefront Journal covers spread out across a wall displaying faces from the community. Another wall display highlights various photos and artifacts. The meeting room contains artifacts, books, and an ongoing video presentation. In the midst of all of these displays stands the Archives.

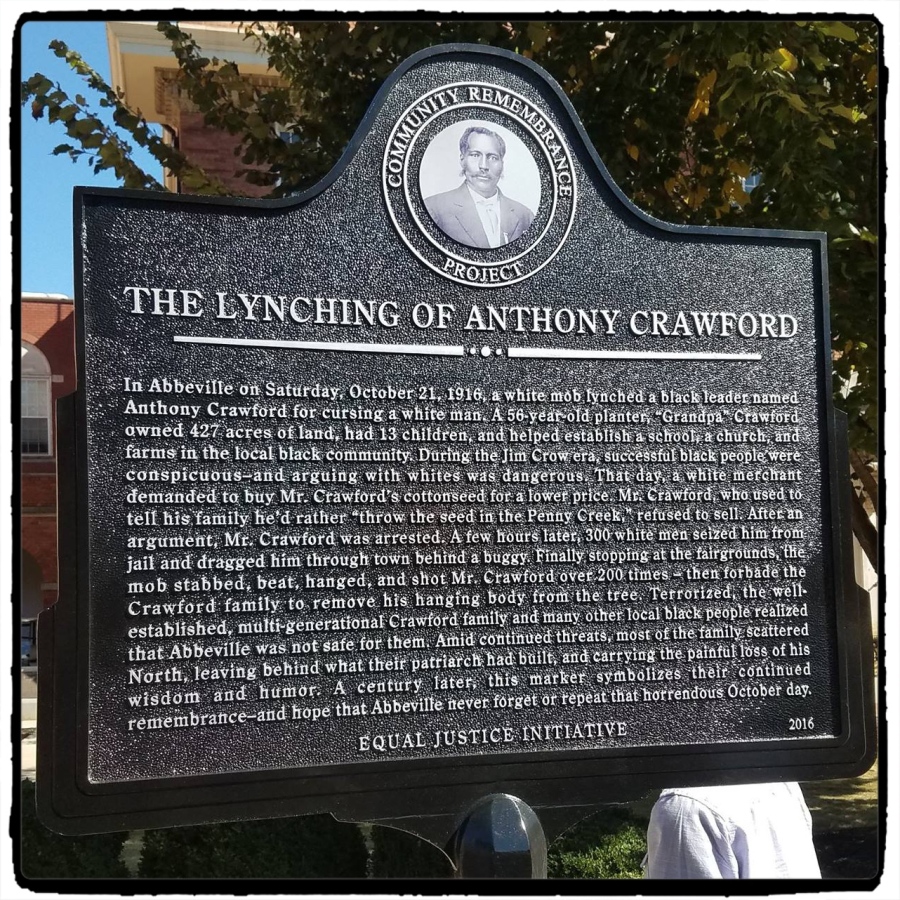

Lecture one was Abbeville, South Carolina to Evanston and the Long Road to Recognition and Reconciliation. Lecture two was Pan-Africanism: Cuba and the Fight Against Colonialism. Session three was The Black Vote: What Just Happened—and What Do We Do Now? Sessions were held at Sherman United Methodist Church and at the Evanston Levy Center and was attended by over 175 participants.

Lecture one was Abbeville, South Carolina to Evanston and the Long Road to Recognition and Reconciliation. Lecture two was Pan-Africanism: Cuba and the Fight Against Colonialism. Session three was The Black Vote: What Just Happened—and What Do We Do Now? Sessions were held at Sherman United Methodist Church and at the Evanston Levy Center and was attended by over 175 participants.

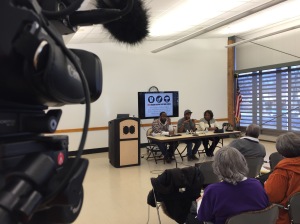

In partnership with the Evanston Chapter NAACP, The African American History and Genealogy Consortium and the Haitian Congress to Fortify Haiti, three community wide panel discussions were shared at the 4th Annual Black History Lecture Series event. Held on three consecutive Saturdays, scholars and community members shared their knowledge. All three sessions were filmed and archived at Shorefront.

In partnership with the Evanston Chapter NAACP, The African American History and Genealogy Consortium and the Haitian Congress to Fortify Haiti, three community wide panel discussions were shared at the 4th Annual Black History Lecture Series event. Held on three consecutive Saturdays, scholars and community members shared their knowledge. All three sessions were filmed and archived at Shorefront.

So we celebrate Juneteenth, celebrating African American freedom, achievement, self-development and remember that we must show respect for all cultures. As Juneteenth celebrations continue across this nation, the events that have transpired back in 1865 in Texas, will not be forgotten. For all of our roots tie back to this fertile soil from which many were delivered to, worked on, built on, and we all should celebrate, a national day of pride that is embodied as Juneteenth.

So we celebrate Juneteenth, celebrating African American freedom, achievement, self-development and remember that we must show respect for all cultures. As Juneteenth celebrations continue across this nation, the events that have transpired back in 1865 in Texas, will not be forgotten. For all of our roots tie back to this fertile soil from which many were delivered to, worked on, built on, and we all should celebrate, a national day of pride that is embodied as Juneteenth.