— By Dino Robinson

Organized and to the point, Esther Pringle Weldon sat at her folding table behind several organized stacks of albums, obituaries, photographs and other family memorabilia. She is surrounded by photographs in her living and dining rooms meticulously displayed on the family piano, the couch and on chairs representing five generations of the Pringle family. On a folded sheet of paper is a hand-written account of her 92-year family history in Evanston in the very house her father built at 1827 Grey, Evanston.

Charles George and Carrie Watt Pringle left Level Land, South Carolina (Abbeville) in 1913 with four children, James, Spurgeon, Ruby and Thelma who was born en route. The Pringle family’s intended destination was California. However, after visiting friends in Evanston, IL, the Pringles decided to stay. Evanston offered land to build a home and available employment opportunities.

In 1916, Charles Pringle built the family home at 1827 Grey, the same home were Esther Pringle still resides. There was a total of seven children in the family with birth dates ranging between 1909 and 1924. Esther’s siblings included James, Spurgeon, Charles, Dorothy, Patricia and Howard. Ruby and Thelma passed on early in their lives, at four years and 18 months respectively.

Charles Pringle found employment as a laborer, first as a bricklayer in Evanston then later with the railroad where he shoveled coal in engine furnaces. Their dreams and aspirations were being realized until an unexpected and life-changing event occurred.

“When my father knew he was not going to get better,” Esther says, “he wanted my mother to go back south. She was only 37 when my father passed, and he was 39. But she did not want to go back. She just stepped out on faith and stayed.”

Charles untimely death in 1924 left the Pringle family without a father for his seven children and husband for his wife. Carrie took care of the home but had to find employment as a laundress after her husband passed. With the trust in their faith, Carrie’s ongoing mantra when difficulties arose was, “Let’s pray about it.”

“Before his death, my father kept two promises to her, he built her a home and he purchased her a piano,” Esther says. The Pringle home and piano are central to the Pringle family. “We always had a piano. My mother played church songs on it, the neighborhood kids would come in and play it, and my sisters played it.” Esther added, “Everyone in the neighborhood knew of the Pringle piano. Children who were taking piano lessons would come over and practice, and my brother, Charles, would play the ‘Bogie Woggie’.”

Esther’s daughter, Renee Weldon, would later learn on that same piano and grow to be an accomplished pianist, well regarded in area competitions.

The Pringles worked as a well- organized family. After the death of their father and at the beginning of the nation’s Great Depression era, the older siblings did what was necessary to assist. “My older brothers, James and Spurgeon, had to quit school to help my mother.” Esther says.

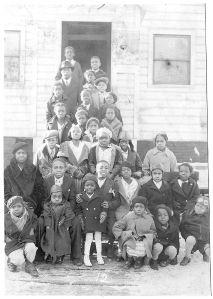

Despite these times, recreational activities took up a big part of their formative years. They often engaged in activities in and around Foster School as well as at Mason Park on Church Street. Esther enjoyed dramatics and poetry at Foster, her church and within the organizations in which she participated. At Mason Park, the Pringles played baseball and hop-scotch. They went to the circus when it was in town, watched parades and went to the Church Street beach. “My brother, Howard, was a lifeguard there at one time,” Esther says.

They often saw movies at the Valencia and Varsity Theaters. “They talked about it being segregated and all, but we all just went to the balconies anyway. My brother, Spurgeon, and one of his friends went onto the first floor. The ushers tried to put him out, and of course when one of them put their hands on him, a fight broke out. They put my brother in jail, but my mother got him out and placed a suit against the judge who put him there and ended up getting her bail money back.”

As music was part of the Pringle family, so was education. Whether in school or out, reading was important. It was expected to always read and become knowledgeable about something. “Even though my older brothers had to drop out of school, they later took correspondence courses.” Esther says. “James eventually went back to high school to get his G.E.D.”

Let’s pray about it.

The foundation of the Pringle family lays within their faith. Throughout their family history in Evanston, members of the Pringle family have been involved with Mt. Zion Baptist Church, Second Baptist Church, Long Memorial Baptist Church, which later merged with Springfield Baptist Church, and New Hope Christian Methodist Episcopal Church.

Charles and Carrie have been instrumental in the formation of the early New Hope C.M.E. Church when it was located at West Railroad (Green Bay Road) and Asbury Avenue in what was then Ford’s Hall. “Now there is a filling station there,” says Esther.

“My parents helped to organize New Hope Church. But we also went to Mt. Zion Baptist Church on Clark Street and we were baptized at Mt. Zion.” Esther continued as she circled among her photographs and other memorabilia, “As a family, we became more active at New Hope when it moved over to Grey and Emerson. But we were active with a lot of churches, because that was where all of our activities were.” Many of the youngster’s as well as other youth went to many church-organized picnics and hayrides.

Most of the Pringles went to Foster school and the high school with the exception of James and Spurgeon who went to Dewey School and later to Boltwood Junior High School. Each of the surviving seven siblings made their own stamp on life while in Evanston and throughout their adult lives.

James “Jay” Pringle, who had been born in 1909 in South Carolina, used to play on the Flashers basketball team at the Emerson Street YMCA. He also played golf and worked as a caddie. His first job was at the Evanston Hotel and later worked as a Pullman Porter for 37 years. After his retirement, he volunteered as a crossing guard for Dewy School at Lake and Asbury for 14 years until his health gave way.

A little known bit of history of Penny Park bordering Lake, Florence and Ashland, is that after James passing in 1989, a name that was considered for the park was “Pringle Park” in memory of James Pringle and his community service in the area.

Esther’s other siblings went on to be productive in all of their aspirations in community engagement and career choices.

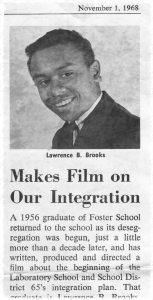

Esther Pringle Weldon, born in 1922, attended Foster School, Evanston Township and Roosevelt University. She worked in a factory for a “very short time” during WWII, then as a daycare provider for the nursery school at Bethel AME Church. She later worked with the Chicago Board of Education and then at Northwestern University in the Tech Library. She was later transferred to Tech Administration until her retirement after 22 years.

From an early age, Esther was active with New Hope Church where she took an interest in poetry. She represented the church in youth contests at St. Paul C.M.E. in Chicago. At the age of fifteen, she won first place in the competition. She was also involved in other organizations such as the Girls Reserve and the Junior League. During the eight years of her involvement in the League, she served as President of her chapter for a number of years. “One of the fundraisers we often held were plays. I often played the villain in the mystery plays,” she laughed.

Today, Esther is the only surviving sibling of Charles and Carrie Pringle. Family members are either interned at Rosehill or Sunset cemetery with the exception of Thelma who is interned in Abbeyville, South Carolina.

The Pringle family was a cohesive family. “As we grew up, we all lived within six blocks from each other.” Esther Says, “We would often walk to each others homes and visit… Those were the good-ole-days.

“We spent most of our time growing up on the ‘west-side’”, Esther reflects. “We didn’t have much money, so we didn’t go downtown often. We didn’t run into too much segregation because we stayed out, by choice, of that type of atmosphere.”

Esther’s daughter, Renee Weldon Wright, was an accomplished pianist and violinist, winning several competitions. Upon graduating from ETHS, she attended Grinnell College in Iowa on the Le Jeune Fisher-Vera Bentley Music Scholarship. Renee was the first African American recipient of that scholarship. She left music and went on to obtain a Masters Degree in Urban and Regional Planning. She later became Director of Corporate and Foundation Relations at Delaware State University and opened her own business, The Pringle Group, specializing in grant writing, business plans and marketing. Recently, Renee earned her M.B.A. at Delaware State University.

The Pringle legacy of struggles and accomplishments resembles that of many who grew up in the same time period. The responsibility lies with us to record and share these experiences with future families. Esther gives credit for the success as a family to her mother. “My mother was a smart person. You couldn’t put anything past her.” Esther says “She was a praying mother. When any difficulties came before her, she always said ‘Let’s pray about it’. She always stepped out on faith.”

Charles and Carrie Pringle stepped out on faith, leaving family in Level Land, South Carolina with the goal of migrating to California. Their chance decision to stay in Evanston and build a home, laid the foundation of a new chapter in the Pringle family legacy. Esther takes pride in the 92-year-old house her father built in 1916. “Not too much has changed,” Esther says. “The siding, the back room, and the front façade, but it is the same space where we all grew up.”

Note: Article first appeared in the original printed Shorefront Journal, Volume 6, Number 4, Summer 2005 and has been edited for length.